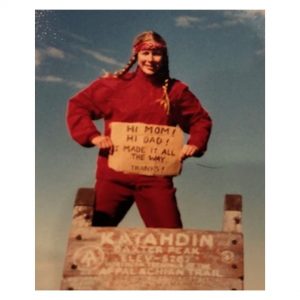

About a hundred years ago, I hiked the Appalachian Trail (AT) from Springer Mountain in Georgia, to Mt. Katahdin in Maine. I finished those 2,190 miles in 5 and ½ months. As one of the first 100 or so women to earn the title of ‘thru-hiker,’ I was about as full of myself as someone who attends a prestigious college, and never quite gets over it. At parties, I would endeavor to casually slip my AT merit badge into the conversation, as subtle as a brick through a window. I was, as they say, “all that, and a bag of chips.”

Or so I thought.

Years later, I learned that Emma “Grandma” Gatewood had been the first woman to hike the AT, at the age of 67. Oh, and she went on to thru-hike two more times, at the ages of 73, and 75, respectively.

In Keds sneakers.

As I struggled to accept this humbling fact, a blind recovering alcoholic, twice my age, completed the AT with his seeing-eye dog, Orient.

I had a long way to fall and fall I did.

By necessity, I became more curious about self-awareness, and ultimately, I became a student of the burgeoning concepts of leadership and coaching. I went to work for Outward Bound as a wilderness guide and encouraged others to ignore the self-imposed twin tricksters of ego and doubt. I ran corporate leadership programs around the world and led development departments for large multi-national firms. I met and fell in love with, the field of what was then called “diversity,” one that has now broadened to deal more directly with inclusion, equity, and unconscious bias, concepts I now teach virtually with leaders across a number of firms.

More recently, as America’s unpaid bills of systemic prejudice have come due, I have found myself returning frequently to the lessons learned during my AT thru-hike, squeezing every drop of juice from that lived adventure. I remember, through the poetic haze of time, the ‘Trail Rules’ and ‘Trail Magic’ that accompanied me up and down those punishing ridges. Only now do I fully comprehend the privileged perch I stumbled from to spend six months on the trail facing chosen hardship, but hardship, nonetheless. I often think of those challenges in my work with corporate leaders as they plumb the depths of meaningful change and inclusion.

Trail Rule #1: Know Exactly Where You Are

In the hush of pre-online connectivity, AT thru-hikers carried well-worn paper maps, wrapped in plastic. Though the ubiquitous white trail markers, or blazes, were usually visible on trees, our maps called up the next day’s journey, cautionary tales of scree or wetlands, and the perception of progress, if not the promise of it. We had no apps for weather, or the next day’s water supply, but we held tightly to knowing where we were, in that moment. Making the next day’s miles, of course, was dependent on knowing where we were starting from each day.

Organizations, too, can nudge their well-meaning intentions closer to impact by measuring where they actually are on the journey to true inclusion and equity, before focusing on an endpoint that may, in fact, have no end. Company-wide surveys and exit interviews are a good place to start. Investing in analytics that track disparities in compensation, hiring, and promotions is also useful, as is taking notice of acts of exclusion or discrimination, and then addressing them by calling people to do better, and to be better.

At Brimstone Consulting, we have a long tradition of using diagnostic tools and practices to paint an accurate picture of the culture that leaders are creating and perpetuating: what is working, and not, and then partnering with them to draw a map, or strategy, of best next steps to improve.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy estimates that only about 25% of intended thru-hikers actually complete the journey each year, many of them succumbing to injuries, blisters, exhaustion, and the daunting realization that whimsy has become a millstone.

According to Deloitte, the percentage of organizations that are actively committed (reaching a level “4” on their inclusive culture maturity model) to inclusion and equity is a woeful 12 percent, when compared to the 71 percent who enthusiastically state their inspirations for the same. Hard work, to be sure.

As with maps, there are no straight lines in the work of creating more just and inclusive workplaces. The work of change, at the heart of all inclusion efforts, can be alternately exhausting, discouraging, and exhilarating. The trick is to keep moving forward with purpose and tenacity, over time, bringing people along the way, knowing where you are right now while also holding a vision of a distant summit.

Only now do I fully comprehend the privileged perch I stumbled from to spend six months on the trail facing chosen hardship, but hardship, nonetheless. I often think of those challenges in my work with corporate leaders as they plumb the depths of meaningful change and inclusion.

Trail Rule #2: Care for People, Starting with Yourself

In the year that I thru-hiked the AT, the Smoky Mountains were slammed in early spring with a record-breaking five feet of snow. Almost as unfit as I was naïve, I was burdened with unnecessary pack weight (a hunting knife, frying pan, and a quart of Dr. Bronner’s Liquid Castile Soap, none of which saw the first 200 miles), inadequate clothing (hey, I thought the South was all peach farms and Spanish moss) and a thick-headedness particular to youth. Despite the exhortations of my hiking partner, I refused to stretch in the chilly mornings, anxious only to jump headlong from my sleeping bag to the warmth that comes with moving. In short order, my ankles swelled cartoonishly, our hiking pace became glacial, and the chill in the air was a perfect complement to the one between him and me. My obstinance, and lack of self-care, had let us both down and we were forced to spend a languid week of convalescence in Hot Springs, NC, for my tendonitis to improve enough so that we might continue north.

Inclusion and equity work is equal parts altruism, common sense, and business smarts. According to a growing number of research studies, organizations that effectively leverage diversity in their teams outperform competitors on a number of fronts, including EPS, engagement, ideation, and innovation. (Note to self: The keyword is leverage; simply having a diversity of people on a team means next to nothing. It is the engagement, respect, meaty project assignments, and learning from difference that creates the lift.)

At the same time, leaders who are actively engaged in the work need to remember that there can be no effective long-term altruism without a commensurate focus on self-care. For executives who have likely advanced due to technical skills and know-how, taking on the mantle of inclusion champion can elicit feelings of incompetence and awkwardness. Engaging in meaningful dialogues about diversity and inclusion can invoke an emotional hyper-vigilance for many leaders. What if I offend someone? What if I say something wrong? Maybe I should just lay low? Managing these vulnerabilities requires time and effort. It is tempting to give in to the impulse to stay defended or to give up if immediate progress doesn’t show itself. One foot in front of the other. It’s the proverbial marathon and not a sprint.

#3: Hike Your Own Hike

At one point in our AT thru-hike, my partner and I lost sight of the white blazes and mistakenly hiked on a secondary trail parallel to the AT for a mile or so. ‘Purists’ that we were, we backtracked and re-hiked the missed mile, hellbent on stating correctly that we had walked every step.

Others were less ‘pure,’ and missed minor sections, or ‘slack-packed’ by paying a driver to deliver their heavy pack to a trailhead at day’s end, ensuring a lighter and faster way to make miles. We were hiking snobs, convinced that there was only one ‘true way’ to be a thru-hiker. To us, if a hiker cheated miles in the forest and there was no one around to witness it, it was still cheating.

As the months wore on, though, it became increasingly obvious that worrying about what other people were doing, or how ‘pure’ they were, was a perfectly good waste of time and energy. So what if the couple from Tennessee hitchhiked ahead and miraculously appeared in a shelter logbook four states ahead? Did it really diminish our adventure, or simply give us a fleeting (and false) sense of superiority?

So it is with the work of diversity and inclusion. Comparing one’s organization to the perception of others’ success (remember the 2018 Google ‘walk-out’?) is demoralizing, and we all know where declaring “mission accomplished” too soon can go, as well. All of us travel at our own pace, and each organization has its own particular culture, opportunities, needs, and set of demographics.

There is no corner on the type of leader that is most successful at this work, although an ability to build trusting relationships may be table stakes. Invoke Trail Rule #1 to know where your own organization or team is, and go from there according to what makes sense, so long as the general destination is up.

Trail Magic

In the years since I joined the ranks of AT thru-hikers, I have heard a number of stories of ‘Trail Magic,’ the phenomenon describing unexpected acts of generosity from strangers: offers of food, an outdoor shower, or a ride to the closest town for supplies.

In Pennsylvania, at the halfway mark, an Amish farmer insisted on giving us a crisp $20 bill, a fortune for us at that time, and maybe for him. A former Vermont Governor and his wife had us sleep in their barn and fed us pancakes in the morning. We benefited almost daily from the “cobbknockers” who rose early and inadvertently cleared the trail of cobwebs. Whatever it was we needed most, we often found it without looking, all of it precious psychological fuel to keep us moving forward.

In one of his pivotal speeches, MLK rightly stated that “the road to freedom is a difficult, hard road.” In the same speech, he also spoke of the beauty that comes from being a part of a “beloved community,” and that, “as you struggle for justice, you do not struggle alone.”

If there is ‘magic’ in the worthy yet ambitious effort to include, it is in surrounding ourselves with those who are also invested in making progress, in invoking the courage necessary to bring change, and in using humor and grit to keep moving. While there are indeed moments of frustration and weariness in moving the needle of inclusion, there also seems to be a virtuous cycle of comradery, respect, and satisfaction for leaders who are in the boat together, pulling an oar and advancing the cause, if ever so slowly.

Bill Erwin, the aforementioned blind AT thru-hiker, told an interviewer that he sometimes fell 50 times in a day, wearing shin guards to try to protect himself. He suffered from almost constant injuries and when asked how he knew where he was on the Trail, he replied, “I don’t.”

Bill Erwin is the stuff of legends. Ordinary leaders, at all levels, who get up every day and endeavor to widen the aperture and see the ‘other’ when they hire, promote and engage, those are the leaders I want to walk alongside.

Even if the place of arrival is always just beyond the next ridge.